Every year, thousands of patients in the U.S. and Canada face delays in life-saving treatments-not because the medicine doesn’t exist, but because it’s simply not available. Generic drugs, which make up over 90% of all prescriptions filled, are the backbone of affordable healthcare. Yet they’re also the most common cause of drug shortages. In 2020, nearly 200 generic drugs went out of stock. By 2023, the number of active shortages remained stubbornly high, with sterile injectables like antibiotics, anesthetics, and chemotherapy agents leading the list. Why does this keep happening? The answer isn’t one single mistake. It’s a broken system built on thin margins, global dependencies, and a lack of backup plans.

Manufacturing Problems Are the Top Cause

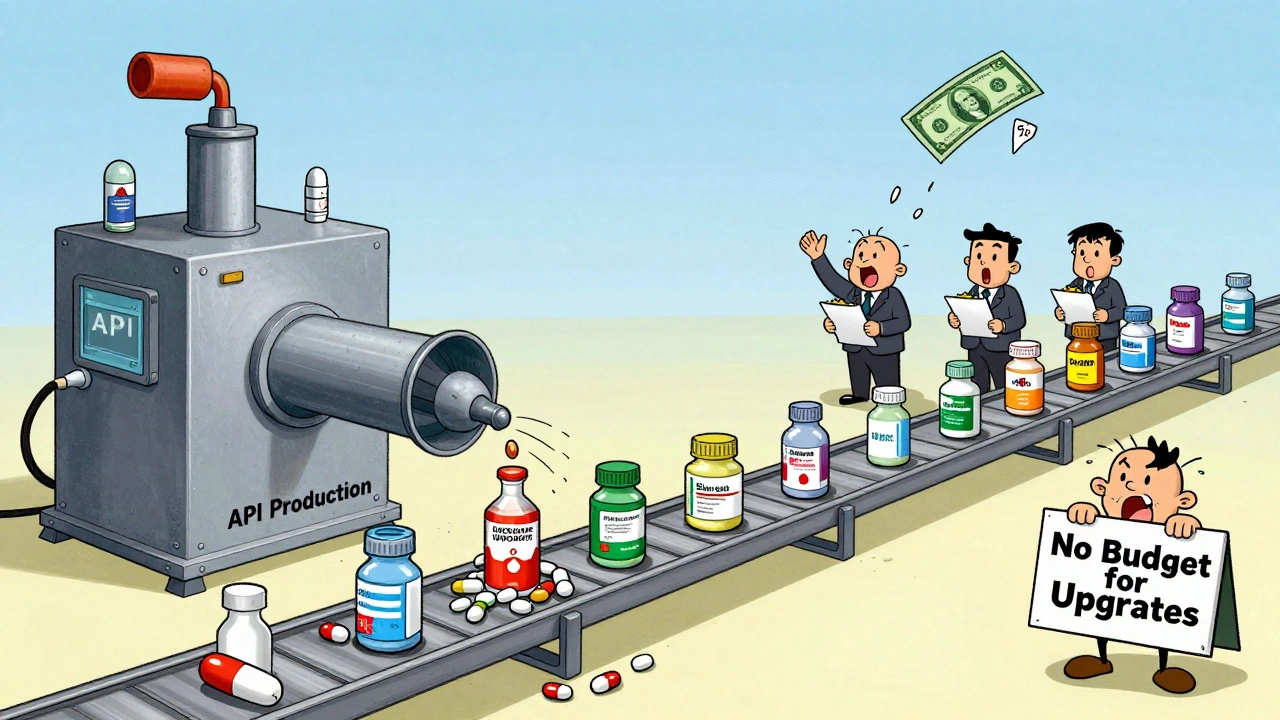

More than 60% of all drug shortages trace back to manufacturing issues, according to FDA data from 2020. This isn’t about occasional glitches. It’s about repeated, systemic failures. A single contaminated batch can shut down an entire production line for months. Equipment breakdowns, poor sanitation, or failure to meet quality standards trigger inspections, shutdowns, and mandatory repairs. These aren’t minor hiccups-they’re full stoppages.

Many of these facilities are old. Some were built decades ago and haven’t been upgraded to modern standards. Keeping them running requires constant investment. But with generic drug prices dropping year after year, manufacturers can’t afford to spend on upgrades. One plant might be making ten different generic drugs on the same line. If one product fails inspection, the whole facility shuts down-even if the other nine drugs are perfectly safe. That’s called a single point of failure. And there are too many of them.

Zero Buffer, No Safety Net

Unlike other industries, pharmaceutical manufacturing doesn’t build extra stock. Why? Because there’s no profit in it. Generic drugs are sold at rock-bottom prices. Companies operate on margins as low as 5-15%, compared to 30-40% for branded drugs. If you make extra pills and they sit on a shelf for six months, you’re losing money. So manufacturers run lean. They produce just enough to meet current demand. No surplus. No backup.

This model works fine until something goes wrong. A hurricane knocks out a factory in Puerto Rico. A fire shuts down a packaging line in India. A regulatory inspection halts production in China. When that happens, there’s no reserve. No emergency stockpile. No Plan B. The system collapses because it was never designed to handle disruption. It was designed to be cheap-and that’s exactly what made it fragile.

Global Supply Chains, Local Consequences

Eighty percent of the active ingredients in generic drugs-known as APIs-are made in just two countries: China and India. That’s not a coincidence. Labor is cheaper. Regulations are looser. But it’s also incredibly risky. One political dispute, one export ban, one pandemic, and the entire supply chain trembles.

During the early days of COVID-19, lockdowns in China halted API shipments. Hospitals in the U.S. ran out of propofol, the anesthetic used in surgeries. Nurses had to delay procedures. Patients waited. Some were sent home. That wasn’t an anomaly-it was predictable. And it happened again in 2022 when a major API supplier in India failed an FDA inspection. The drug didn’t disappear overnight. It vanished slowly, over weeks, while hospitals scrambled to find alternatives.

And here’s the kicker: many of these API factories are the only ones in the world making that specific ingredient. If one plant goes down, there’s no other source. That’s called sole sourcing. One in five drug shortages involves a sole-sourced product. No competition. No alternatives. Just one supplier holding the entire system hostage.

Consolidation Killed Competition

Twenty years ago, dozens of companies made generic drugs. Today, just a handful control most of the market. Three big pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs)-Express Scripts, CVS Health, and Optum-control about 85% of prescription drug spending in the U.S. They don’t just process claims. They decide which drugs get covered, which ones get pushed to the front of the line, and which ones get dropped entirely.

These companies negotiate prices with manufacturers. To win a contract, manufacturers must undercut their rivals. The result? Prices keep falling. Margins shrink. Smaller companies can’t compete. They close up shop. The ones that stay are forced to cut corners-on quality, on staffing, on maintenance. It’s a race to the bottom. And when the last remaining supplier runs into trouble, there’s no one left to step in.

The number of registered drug manufacturing sites in the U.S. has dropped by nearly 30% since 2010. Fewer factories. More drugs per factory. More risk. Less resilience.

Why Canada Handles It Better

Canada faces the same global supply chain issues. Same API sources. Same low margins. But they don’t have the same level of shortages. Why? Because they treat drug supply as a public health issue-not a market competition.

Canada has a national stockpile of critical drugs. When a shortage hits, they pull from it. They also have a centralized system where regulators, hospitals, pharmacies, and manufacturers communicate directly. When a drug is at risk, everyone knows within hours. They can reroute shipments, adjust dosing, or activate backup suppliers before patients are affected.

In the U.S., there’s no such coordination. The FDA tracks shortages, but doesn’t control production. PBMs don’t share data. Hospitals don’t talk to each other. Manufacturers don’t report problems unless forced to. And even then, the reasons are often vague. One in four shortage reports in the U.S. don’t even say why the drug is gone. No transparency. No accountability.

The Economic Trap

Here’s the cruel irony: the drugs most likely to go missing are the ones we need the most. Antibiotics. Blood pressure meds. Insulin. Chemotherapy. These are low-cost, high-volume drugs. They’re not glamorous. They don’t make headlines. But they keep people alive.

Manufacturers don’t want to make them because the profit is too small. Why invest millions in FDA compliance for a drug that only earns $0.10 per pill? It’s not rational. But it’s the market. And until we fix the incentives, the shortages will keep coming.

Some lawmakers are trying. The RAPID Reserve Act, introduced in 2023, proposes creating a national stockpile of critical generic drugs. It also offers tax breaks to companies that make APIs in the U.S. But these are Band-Aids. The real fix? Pay manufacturers enough to make these drugs sustainably. Reward them for having backup capacity. Force transparency. Break up monopolies. Stop letting PBMs decide what patients get.

What’s Next?

There’s no quick fix. But there are steps that can help. Hospitals can start tracking their own inventory in real time instead of waiting for suppliers to notify them. Pharmacies can prioritize drugs with multiple sources. Regulators can require manufacturers to report potential shortages months in advance-not after the shelves are empty.

And patients? They can ask. When your doctor prescribes a generic drug, ask: "Is this in short supply? Is there another option?" You might be surprised how often there’s an alternative. And if you’re on a long-term medication, talk to your pharmacist about switching to a different manufacturer. Not all generics are made the same.

The system is broken. But it’s not inevitable. People are working on solutions. The question is whether we’ll act before the next shortage leaves someone without the medicine they need.

Nigel ntini

It’s wild how we treat life-saving meds like commodities instead of public goods. The fact that a single contaminated batch can shut down half the nation’s antibiotics is a systemic failure, not bad luck. We need mandatory buffer stocks, not just ‘hope and pray’ supply chains.