For someone who’s received a new kidney, liver, heart, or lung, the miracle of transplantation comes with a heavy price: lifelong immunosuppressant drugs. These medications keep the body from attacking the new organ, but they also turn the immune system into a weakened defense system. The trade-off is real - without them, the transplant fails. With them, you’re at higher risk for infections, cancer, kidney damage, diabetes, and a host of other problems that change daily life.

How Immunosuppressants Work - And Why They’re So Dangerous

Immunosuppressants don’t just calm the immune system. They shut down specific parts of it. The most common drugs fall into four groups:- Calcineurin inhibitors - Tacrolimus (Prograf) and cyclosporine (Neoral) block T-cells from triggering rejection. Tacrolimus is used in over 90% of U.S. kidney transplants because it’s more effective than cyclosporine.

- Antimetabolites - Mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept) and azathioprine (Imuran) stop immune cells from multiplying by cutting off their energy supply.

- Corticosteroids - Prednisone reduces inflammation across the body but causes weight gain, mood swings, and bone loss.

- mTOR inhibitors - Sirolimus (Rapamune) and everolimus (Zortress) slow cell growth, helping avoid kidney damage but causing mouth sores and high cholesterol.

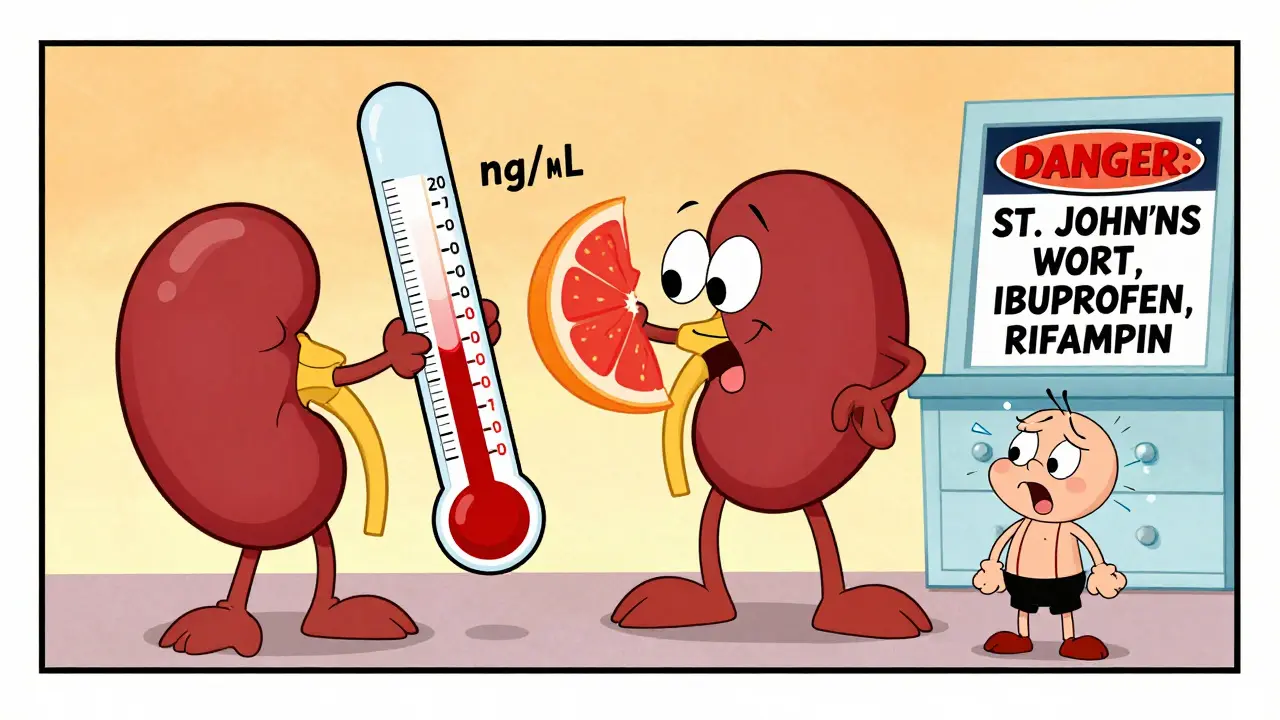

These drugs work differently, but they all have one thing in common: a very narrow window between doing their job and causing harm. For example, tacrolimus must stay between 5-8 ng/mL in your blood during the first year after transplant. Go above that, and you risk kidney damage or tremors. Drop below, and your body starts rejecting the new organ. That’s why blood tests every few weeks aren’t optional - they’re life-saving.

Drug Interactions You Can’t Afford to Ignore

Most transplant patients take 8 to 12 pills a day. That includes blood pressure meds, cholesterol drugs, acid reflux pills, even over-the-counter pain relievers. And here’s the problem: almost every one of those can mess with your immunosuppressants.Tacrolimus and cyclosporine are broken down by an enzyme in your liver called CYP3A4. Anything that blocks or speeds up this enzyme changes how much drug stays in your blood. Common culprits:

- Antifungals like fluconazole can spike tacrolimus levels by up to 200%. That’s a recipe for kidney failure or nerve damage.

- Antibiotics like rifampin can slash tacrolimus levels by 90%. That’s a fast track to rejection.

- St. John’s Wort - a popular herbal remedy for depression - cuts tacrolimus levels by half. Many patients don’t realize it’s dangerous.

- Grapefruit juice - yes, the healthy breakfast drink - blocks CYP3A4 and can dangerously raise drug levels.

Even common OTC meds like ibuprofen or naproxen can hurt your kidneys when combined with calcineurin inhibitors. That’s why you can’t just walk into a pharmacy and pick up something for a headache. Every new medication - prescription, supplement, or herbal - needs approval from your transplant team.

The Most Common Side Effects - And How They Hit Real People

Side effects aren’t just numbers in a study. They’re daily struggles.Nephrotoxicity - Kidney damage from calcineurin inhibitors affects 25-40% of recipients. In 65% of patients who get routine biopsies five years after transplant, there’s visible scarring in the kidney tissue. Some switch to sirolimus to avoid this - and see their kidney function improve. One Reddit user, u/LiverSurvivor, said switching from tacrolimus to sirolimus raised their GFR from 38 to 52 mL/min over 18 months. But they got constant mouth ulcers and had to start statins for high cholesterol.

New-Onset Diabetes After Transplant (NODAT) - About 20-30% of kidney transplant patients develop diabetes within five years. Tacrolimus carries a higher risk than cyclosporine. This isn’t just about insulin shots - it means tighter diet control, more blood sugar checks, and higher risk of heart disease and nerve damage.

Metabolic chaos - Steroids like prednisone cause moon face, buffalo hump, weight gain (15-20 pounds in six months), and bone thinning. One NHS survey found 47% of heart transplant patients said they didn’t recognize themselves in the mirror. Osteoporosis hits 30-50% of long-term recipients, with fracture risk rising sharply after 10 years.

Infections - Your immune system is on mute. That means colds can turn into pneumonia. A simple cut can get infected. You can’t eat raw sushi, rare steak, or unpasteurized cheese. Listeria from deli meats can kill you. One transplant center found 85% of recipients had at least one serious infection in the first year.

Cancer risk - Non-melanoma skin cancer affects 23% of liver transplant patients. Overall, transplant recipients have a 2-4 times higher risk of cancer than the general population. HPV-related cancers - like throat and cervical cancer - occur 100 times more often. That’s why annual skin checks and pap smears aren’t optional. They’re mandatory.

Managing the Balancing Act - What Works in Real Life

No one wants to take 10 pills a day. No one wants to live in fear of a fever. But here’s what works:- Use a pill organizer with alarms - One Cleveland Clinic study showed electronic pill dispensers boosted adherence from 72% to 89%. Missing a dose can trigger rejection.

- Get your blood tested on schedule - Tacrolimus levels need checking twice a week at first, then monthly. Skipping tests is like driving blindfolded.

- Ask about steroid-free protocols - 85% of top transplant centers now try to stop steroids within 7-14 days for low-risk patients. That cuts weight gain, diabetes, and bone loss by 35-40%.

- Know your triggers - Avoid grapefruit, St. John’s Wort, and unapproved antibiotics. Always tell your pharmacist you’re a transplant patient before filling any prescription.

- Report symptoms early - Fever above 100.4°F? Diarrhea lasting more than two days? Unexplained bruising? Call your transplant team immediately. Don’t wait.

One patient from Cleveland Clinic said, “I used to think the transplant was the finish line. Turns out, it’s the start of a whole new marathon - and you can’t stop running.”

What’s Changing - And What’s Coming

There’s hope on the horizon.In 2023, the FDA approved voclosporin (Lupkynis), a new calcineurin inhibitor with less kidney toxicity than tacrolimus. In trials, it cut nephrotoxicity by 24% while keeping rejection rates low.

Belatacept (Nulojix), a drug that blocks immune signals instead of poisoning cells, shows promise. In a 7-year study, patients on belatacept had 30% fewer heart attacks and 25% less cancer than those on tacrolimus. The catch? Higher rejection rates early on - so it’s only for certain patients.

And then there’s the holy grail: immune tolerance. Researchers are testing therapies that teach the body to accept the new organ without drugs. In a 2023 study, 15% of kidney transplant recipients achieved operational tolerance - meaning they stopped all immunosuppressants and stayed healthy. It’s not common yet, but it’s real.

For now, though, most patients still need drugs. And the cost? In 2022, tacrolimus alone generated $2.1 billion in global sales. But generics are coming. Tacrolimus patents expire in 2025 - which could slash prices by half.

The Hard Truth

The 10-year survival rate for kidney transplant recipients is 65%. For someone the same age who never had a transplant? It’s 85%. That gap isn’t because the surgery failed. It’s because of the drugs that keep the organ alive.There’s no perfect solution. Every drug has trade-offs. Every side effect changes your life. But for most people, the choice is clear: take the meds and live with the consequences - or stop them and lose the transplant.

The best thing you can do? Stay informed. Stay in contact with your team. Never assume a new pill is safe. And remember - you’re not alone. Over 186,000 Americans are living with a functioning transplant right now, all managing the same impossible balance. It’s not easy. But it’s possible.

Can I take over-the-counter painkillers like ibuprofen after a transplant?

No, not without approval. NSAIDs like ibuprofen and naproxen can cause serious kidney damage when combined with calcineurin inhibitors like tacrolimus. Even occasional use can worsen kidney function. Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is usually safer, but you still need to check with your transplant team before taking any OTC medication.

Why do I need to avoid grapefruit juice?

Grapefruit juice blocks the enzyme CYP3A4, which your liver uses to break down tacrolimus and cyclosporine. This causes drug levels to spike dangerously - sometimes by 200% or more - increasing your risk of kidney failure, nerve damage, and other toxic side effects. Even small amounts can have this effect, so it’s best to avoid grapefruit and its juice entirely.

Is it safe to stop taking immunosuppressants if I feel fine?

Absolutely not. Stopping immunosuppressants - even if you feel great - almost always leads to organ rejection. Most rejections happen without warning symptoms. In fact, 22% of late graft losses are due to patients skipping doses or stopping medication entirely. Your body doesn’t “get used to” the new organ. It needs constant suppression to prevent attack.

What are the signs of organ rejection?

Rejection doesn’t always cause obvious symptoms. For kidney transplants, it might mean rising creatinine levels, swelling, or reduced urine output. For liver transplants, it could be jaundice, dark urine, or fatigue. Heart transplant rejection may cause shortness of breath or irregular heartbeat. The most reliable sign? A change in blood test results. That’s why regular monitoring is non-negotiable. Never wait for symptoms to appear.

Can I get vaccinated after a transplant?

Yes - but only certain vaccines. Live vaccines (like MMR, varicella, or nasal flu spray) are dangerous because your immune system can’t handle them. Inactivated vaccines (flu shot, pneumonia, COVID-19, tetanus) are safe and strongly recommended. You should get vaccinated before transplant if possible. After transplant, wait at least 3-6 months and always get approval from your transplant team before any shot.

How often do I need to see my transplant team?

For the first year, expect visits every 1-4 weeks, with frequent blood tests. After the first year, most centers require monthly visits for the next two years, then every 3-6 months. Even if you feel fine, skipping appointments increases your risk of undetected rejection or drug toxicity. Most U.S. transplant centers require you to live within 2 hours of the facility for the first year for emergency access.

Are there alternatives to lifelong immunosuppression?

Currently, no - except in rare cases. Identical twin donors are the only scenario where immunosuppression can be safely avoided. Researchers are testing immune tolerance therapies - like regulatory T-cell infusions - that have allowed 15% of kidney transplant recipients to stop all drugs after 2 years. But these are still experimental and only available in clinical trials. For now, lifelong medication is the standard.

What Comes Next

If you’re a transplant recipient, your next steps are simple but critical:- Review your medication list with your pharmacist - every pill, every supplement.

- Set phone alarms for every dose - no exceptions.

- Schedule your next blood test and clinic visit - don’t wait to be reminded.

- Start wearing sunscreen daily - skin cancer risk is real and rising.

- Join a support group - you’re not alone, and hearing others’ stories helps more than you think.

The goal isn’t just to survive. It’s to live - fully, safely, and with as few side effects as possible. That means staying sharp, staying informed, and never letting your guard down.

Elizabeth Cannon

i swear i thought i was the only one who had to avoid grapefruit like it was poison. my tacrolimus levels went nuts the first time i had a glass. now i drink orange juice and pretend i'm in florida. 🍊